This weekend there were two art book fairs in London. At the Whitechapel was the achingly official London Art Book Fair, and at Oxford House was the achingly unofficial Publish and Be Damned. I found one thing at each which I want to put together.

(un)limited store had a stand at Publish and Be Damned. They’re a French publisher that produces artist books, objects and prints. I like the way they don’t differentiate too heavily between these three categories: the objects all have ISBNs like books, for instance, and come boxed and labeled to show they’re part of or published by the (u)ls project.

David Lasnier is one of the artists whose objects they publish. I bought a rubber stamp by him which reads ‘stamped’.

You can’t go wrong with it. So far I’ve stamped the corner of my desk, the edge of my laptop (it might rub off), the box from the stamp, many pieces of paper, my teapot, my hand and some glass jars. It’s very straightforward. If something’s been stamped it says so, if it hasn’t it doesn’t. And the word is continually there regardless, embossed in rubber in its negative form, ready to be removed from its cardboard box, inked and stamped, and wherever it’s stamped it will necessarily apply. Its exquisite circularity reminds me of a couple of other things:

- the signpost in the river that read ‘please do not moor boats to this signpost’, though it seemed to have no other function than to say that;

- the rubbish bin I saw in a park with a notice on it saying ‘please put litter in the bin’, with a clip art picture of a bin underneath;

- the lizard I saw at the zoo who had somehow got underneath the sign for his own species and was lying flat with arms and head coming out the top of the sign and legs and tail coming out of the bottom as if to very precisely label himself;

- the Urquhart print I saw at the Whitechapel on Saturday.

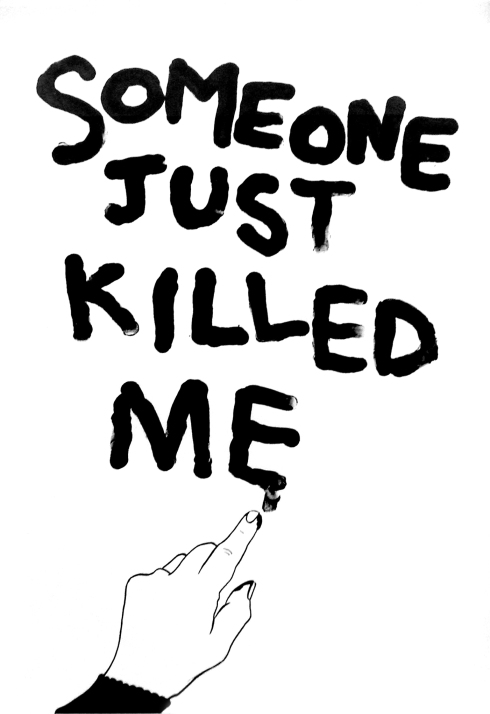

One the wall behind Rocket Gallery’s stall at the London Art Book Fair there was a black and white print by Donald Urquhart with the words ‘SOMEONE JUST KILLED ME’ written messily in thick letters across a white background. At the bottom of the image, where the phrase ends, an outstretched hand with its forefinger dipped in the ink/blood of the message indicates that the words have been daubed with a fingertip. The final stroke of ‘ME’ smudges downwards, presumably as the writer slumps towards his death.

The killing – the infliction of the fatal wound – has taken place before the writing begins. There’s time between being killed and dying. But the victim writes as if from within death, as if he is already dead, with his murder already completed in the past perfect tense. For the statement to be true, the phrase needs to be completed and its writer needs to die. In the drama of Urquhart’s print these parallel processes are timed impeccably: the writer slumps just as the final letter is being completed. As though one were the cause of the other, no sooner is the description complete than does the thing it describes become actual.

Now I think about it, the dark inevitability with which this text meets its object at their mutual end reminds me of a stretch of BBC wildlife footage I saw a few months ago. In slow motion a lion and its prey gracefully close the curve between them as though they were lovingly rehearsing a familiar dance, and as their bodies join each seems willingly to assume a new relation to the other; one pierced and flayed, the other engrossed and taut; both in completion of one another.

And then there’s John Barth’s short story Life Story, in which the writer and written have to make amends of some kind if they’re to let the story end.

1 comment

Comments feed for this article

October 11, 2009 at 2:58 pm

THIS « Homologue

[…] Like a Simile […]